Capturing learning from a Typhoon Odette Community-led Humanitarian Action

Sitio Lawigan, Barangay Salog, Socorro, Surigao del Norte

“Mora’g buhawi (like a hurricane),” was how barangay chairman Jorlito Bayeta, 62, described their Rai/Odette experience in Sitio Lawigan, Barangay Salog, Socorro, Surigao del Norte.

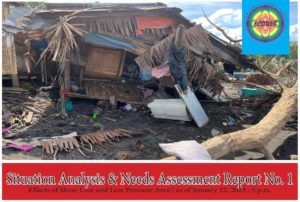

This was a major shock for this community which is tucked safely in one of the many small islands that make up Bucas Grande. They all thought they are safe from typhoons based on their past experiences. Even typhoon Yolanda was not able to damage their fishing village.

“Wayay bayod.” No big waves here. This was the reason why the pioneers chose this place to build a new community. Their grandfathers were fishermen who found this peaceful coast and decided to migrate here from the mainland.

But Odette revealed an ugly side of this secluded cove. The winds formed a funnel, uprooting houses upwards and dumping them in the sea.

It makes sense. This village of 55 families is at the skirts of a lagoon surrounded by high mountains. The strong winds were contained by the mountain, thus forming a funnel, much like a twister. None of the houses were saved, and none of the boats survived the onslaught.

Today, Sitio Lawigan looks like a construction site. Yes, you can see shoes and pants at the bottom of the sea, and abandoned televisions sets and damaged refrigerators on the shore, along with piles of GI sheets salvaged from nearby islands. But mostly, you can see carpenters building small houses. There is an unmistakable sense of recovery, of residents though without resources deciding they need to work together to regain their normal life.

“We survived the worst,” was how the group described it with genuine laughter. “Mostly because people were kind and helpful.” Yes, strangers came in boats bearing much needed food packs and water.

“Private individuals. Families. Friends of our neighbors. They came to help.” Cap. Bayeta explained. “But mostly, people helped one another. Nagtinabangay was the word they used.

But when the Survivor and Community Led Response was introduced by ECOWEB during its visit in the last week of February, the people are ready to work together. Lawigan was referred by Pastor Marlon Abacahen who had been doing organizing work in these islands.

The first sclr support here was the cash assistance to the self-help group that was divided into 2,200 pesos per family. “it was small, but it greatly helped us with our most urgent need at that time.” Arge Bayang, a 41 year old fisherman, declared.

What they did with the amount? They mostly invested.

Investment came in the form of buying ingredients for a small business – a bananaque stand and vinegar from coconut wine. This is shared by a Cathima Bajeta, a young mother.

Investment came in the form of buying gasoline for their fishing boats, or spare parts to repair the engine of their pump boats. It also came in the form of paying for the tuition of a college student. Mostly, they bought materials for their houses – GI Sheets, sacks of cement, plywood.

“No one else will help us, so we will build our new houses one part a time. Today we have a floor because of ECOWEB’s cash assistance. Soon, we will receive from the government five thousand pesos. That will go to roofs and walls.”

When asked what lessons they learned from the sclr support

- SCLR works because the community was ready for it. Odette did not bring with it international NGOs or UN Agencies. They were left on their own to help each other, assisted by families and relatives. But they mostly depended on one another.

“Even before the typhoon, we have always been a community that helps one another. Now the helping is more obvious. We borrow each other’s boats for fishing. We contribute fuel when we use a boat for marketing. We shared food.” This was shared by one mother, to which every one in the meeting agreed.

This is a pronounced difference when compared to previous experiences of doing sclr in evacuation centers where families did not know each other well, such as our experience (with Duyog Marawi) during the Marawi Siege. The trust-building took time, whereas in an isolated compact community like Lawigan, the trust was already there.

- The use of cash grants allowed responsiveness to multiple and differentiated needs. But most of them invested in livelihoods, shelter, and education, the urgency of the need was the deciding point. Each beneficiary was free to decide what is urgent.

- The survivors are thankful of the lessons in accountability. They are now conscious of documentation, of making sure the expenses are verifiable, and of submitting on time. Chairman Bajeta said, “We are now very careful about recording our expenses since this was a practice of the sclr.”

- Everyone was involved in the decision making – fisherfolks, women, young people. There is no limit to who can attend. “Some even attend even if they already had their head of households present. They just wanted to be part of the conversation,” said one Kagawad.

It was obvious to us even when it was not articulated well that the sclr support served as a psychosocial support. The process of meeting, deciding what to do, doing marketing together, helping each other make reports increased social cohesion and allowed them to recover from the depression after the typhoon.

One sign of social cohesion was the unanimity regarding their need. Livelihoods. They all said.